Register by October 17 to Secure Your Spot!

| Registration Type | Member Price |

|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct.3) | $750 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $850 |

| Registration Type | Member Price |

|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct.3) | $750 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $850 |

| Registration Type | Member Price | Non-Member Price |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct. 3) | $750 | $850 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $850 | $950 |

Not a member? We'd love to have you join us for this event and become part of the Chorus America community! Visit our membership page to learn more, and feel free to contact us with any questions at [email protected].

| Registration Type | Non-Member Price |

|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct. 3) | $850 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $950 |

Think you should be logged in to a member account? Make sure the email address you used to login is the same as what appears on your membership information. Have questions? Email us at [email protected].

| Registration Type | Price |

|---|---|

| Individual Session | $30 each |

| All Four (4) Sessions | $110 |

*Replays with captioning will remain available for registrants to watch until November 1, 11:59pm EDT.

Member Professional Development Days are specially designed for Chorus America members. If you're not currently a member, we'd love to welcome you to this event, and into the Chorus America community! Visit our membership page to learn more about becoming a member of Chorus America, and please don't hesitate to reach out to us with any questions at [email protected].

| Registration Type | Price |

|---|---|

| Individual Session | $30 each |

| All Four (4) Sessions | $110 |

*Replays with captioning will remain available for registrants to watch until November 1, 11:59pm EDT.

| Registration Type | Price |

|---|---|

| Individual Session | $30 each |

| All Four (4) Sessions | $110 |

*Replays with captioning will remain available for registrants to watch until November 1, 11:59pm EDT.

Member Professional Development Days are specially designed for Chorus America members. If you're not currently a member, we'd love to welcome you to this event, and into the Chorus America community! Visit our membership page to learn more about becoming a member of Chorus America, and please don't hesitate to reach out to us with any questions at [email protected].

Choruses seek to foster an open, welcoming culture, but some practices can exclude and cause pain for transgender singers. Here are some steps your chorus can take to avoid them.

For many of us, choruses are where we come together to make music and feel like we’re part of a welcoming community. But that’s often not the case for singers who are transgender. Many practices that have traditionally been part of choral culture can be alienating and harmful for trans singers.

William Sauerland, who teaches at Chabot College in Hayward, California, is focusing his dissertation on the teaching of transgender singers. For many singers he has known and interviewed, “music…was not a place of refuge, it was not a safe space” because of “how gendered their choral experience was.”

Transgender people, as defined for the purposes of this article, are all people whose gender (a deeply held sense of being a woman, man, both, neither, or something else) is different from the sex they were assigned at birth based on physical anatomy. The term includes people who identify as nonbinary, or as a gender other than woman or man.

Welcoming Transgender Singers Online ResourcesFamiliarize yourself with Key Terms that are important to know when working with transgender singers, and may help in digesting this article. Looking for further reading on how to make your chorus culture more inclusive of transgender singers? Please consult our Resource List for Welcoming Transgender Singers companion, compiled by Ari Agha. |

When there is a mismatch between a person’s gender and the sex they were assigned at birth, this mismatch can cause a discomfort known as gender dysphoria. And traditional choral practices that divide singers into gendered categories—referring to sopranos and altos as “ladies” and tenors and basses as “men” or requiring gender-specific clothing—can heighten these feelings of discomfort.

As a genderqueer person, someone who is not either a man or a woman, I myself have experienced gender dysphoria because of my involvement in choral singing. For instance, when I was in grad school, my chorus started asking the "women” to wear dresses. I spent hours carefully crafting an email to my conductor asking to wear a tuxedo instead, explaining that I would not be comfortable in my own skin while wearing a dress. He responded by saying I should think of it as just a uniform. I agonized over whether I could go through with it, but ultimately decided to order the dress. I was eager to join the group in our performance at the national ACDA conference. I distinctly remember putting the dress on for the first time, and I felt sick to my stomach. Then I had to walk outside, see my friends, and perform in public. It was mortifying. Despite the immense joy I got from singing, nothing was worth feeling that way.

Roughly 0.6 percent of the U.S. population is transgender. We face extensive discrimination and high rates of violence. Despite this, we are becoming more visible, with more people identifying as transgender and doing so earlier in life, according to several studies published by the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law.

That means that transgender people are becoming more visible in the choral world as well. In the last few years transgender choirs have been established across North America in locations that include Los Angeles, Boston, Kansas City, San Francisco, Cleveland, and New Hampshire. Several articles on transgender singing have been published. And sessions on transgender singers have been included at the ACDA National Conference, the National Collegiate Choral Organization conference, and the Chorus America Conference. The Transgender Singing Voice Conference was held at Earlham College in January 2017, and the Trans Voices Festival hosted by One Voice Mixed Chorus will take place April 13 and 14, 2018, in Minneapolis.

You may believe there’s no need to work on gender inclusion because there aren’t any transgender singers in your chorus, or maybe because you’re not an LGBTQ+ ensemble. But you can’t tell by looking whether someone is transgender, and trans singers do not sing exclusively in LGBTQ+ groups. There may, in fact, be transgender singers in your chorus, even though you don’t know it.

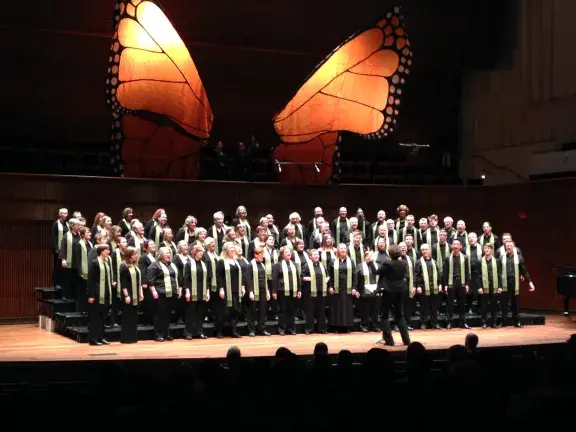

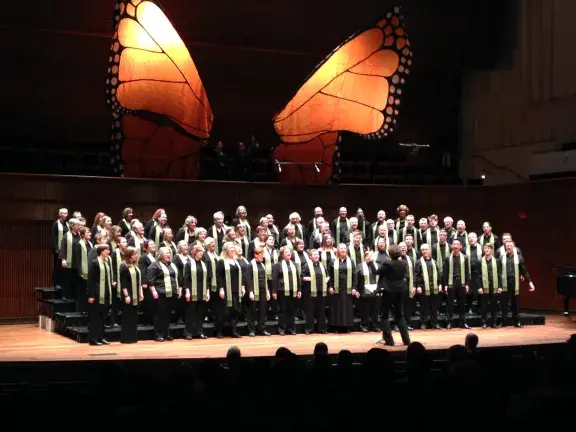

One Voice Mixed Chorus

You also may believe your chorus is already welcoming, but without realizing it or intending to cause harm, you may employ practices and language that exclude and hurt transgender singers. What’s particularly hard, says Joshua Palkki of the Bob Cole Conservatory of Music at California State University, Long Beach, is breaking with tradition: “There’s so much tradition in choral music, and…so many things that just have been done without question, because it’s the way things have always been done.” Choruses must “deal with our history of naming and separating by gender,” says Seattle Pro Musica artistic director Karen Thomas.

Thomas admits she was once one of those who would “just go with the status quo” but she found that “one day it hits you upside the head.” She remembers thinking to herself, “‘If I was a new singer moving to Seattle and I wanted to audition for choirs, I wouldn’t audition for my own choir because I don’t want to wear a dress.’” With the help of a singer task force, the chorus has since created new, more gender-inclusive guidelines for attire along with other adjustments to welcome trans singers. About two weeks after the changes were implemented, Thomas says, “one of our members who had been really quiet and really shy came out as nonbinary in a very public way, because all of a sudden it was safe to do it.”

Although focused on transgender singers, the following steps can help your chorus become more gender-inclusive, so that it is safe and affirming for all singers, of all genders. Avoiding language and policies that reinforce gender stereotypes about men and women will also give cisgender singers, those whose gender fits their sex assigned at birth, more freedom of expression. They are guidelines for creating more space, to make room for singers to bring their whole, authentic selves to your chorus and the music you make together.

For choral leaders new to working with trans singers, questions about how to support trans singing voices are often top of mind. While that is an important aspect that is addressed by these recommendations, the musical training and experience conductors already have provide a strong foundation to do that work. What may require more leaning and effort is creating a welcoming culture throughout your organization.

Transgender people are not a monolithic group—it's hard to make simple recommendations that will serve all of them well—and this list is by no means comprehensive. But it is a place to begin.

1. Include a statement that the chorus is open and affirming to transgender people in organization documentation, and adopt a gender-neutral language statement. “Everybody has to be on the same page, and that starts with a stated intention,” says Danielle Steele, interim director of choral activities at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. Having written statements, she stresses, can ensure clarity and accountability among all stakeholders. Both statements should be widely publicized, including on the ensemble’s website, and in promotional and audition materials.

2. Avoid using gendered language in rehearsal and performance. “Choral teachers should refer to sections, not genders,” says Palkki in his 2017 Choral Journal article “Inclusivity in Action: Transgender Students in the Choral Classroom,” because not everyone who sings soprano or alto is a woman, and not everyone who sings tenor or bass is a man. This practice will also benefit the many cis women who sing tenor. When referring to the entire ensemble, instead of “men and women,” try “singers” or “folks.” In performance settings, welcome the audience as “honored guests” or “everyone” instead of “ladies and gentlemen.”

3. Provide opportunities for singers to tell you their pronouns —and then use them! We may believe we know a person’s gender based on how they look, but to create an affirming ensemble you need “a culture in which people don’t make those assumptions,” says transgender singer and composer Mari Ésabel Valverde. Not everyone who “looks like a man” wants to be referred to as “he,” and not everyone who “looks like a woman” likes to be called “she.” Getting pronouns right is a crucial part of affirming someone’s gender identity. Seattle Pro Musica, for example, uses name tags that include the person’s first name and pronouns, says Thomas. Name tags should be worn by all singers (cis and trans) and the artistic director, so that transgender people are not singled out. It’s also a good idea to collect pronouns in auditions (see No. 11).

4. Consider the implications of gendered language in chorus names. It’s hard for transgender people to know whether a “women’s” or “men’s” chorus will welcome them. “What’s really important,” says Jane Ramseyer Miller, artistic director of One Voice Mixed Chorus in St. Paul, Minnesota, and artistic director-in-residence for GALA Choruses, “is if you call it a women’s chorus, then it needs to be open to all women.” Nonbinary people may rule out these ensembles to avoid being labeled a man or woman by virtue of singing in the chorus. Ensembles can clarify who is welcome with language like “open to all self-identified women” or “open to all cis and trans men and nonbinary people.”

To be inclusive of trans singers, “women’s” and “men’s” choruses also need to select repertoire with voicing that will allow them to participate. Because not all transgender women are on hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and those who are on HRT typically don’t sing in the soprano or alto range (see No. 7), S/A music will require rearrangement. The same applies to “men’s” ensembles wanting to include transgender men.

Excluding gendered words from chorus names allows continued use of S/A or T/B repertoire. Seattle Pro Musica rebranded its small ensembles. Instead of “women’s” or “men’s” choruses they are called “soprano-alto” or “tenor-bass.” “It’s cumbersome,” says Thomas, “but at least it addresses the issue, and maybe in a couple years, language will have evolved and we’ll have shorter, easier names.” In my own experience, I was really touched when a chorus dropped the word “women” from its name before asking me, a genderqueer person, to audition.

5. Don’t assign concert attire by gender or section. Attire is an important way in which all people, trans and cis, represent ourselves to the world, and forcing singers to wear clothes incongruent with their gender identity can be especially uncomfortable for transgender singers who already struggle to have their identities respected. “There is a sense of honesty in choral music that is important,” says Timothy Shantz, chorus master of the Calgary Philharmonic Chorus in Calgary, Alberta. “People wouldn’t want to wear something that misidentifies them.”

Assigning concert attire by section or gender can also be a challenge for cisgender singers. “I do have a couple of female tenors,” says Shantz. “I’m not sure how it came about, but two of them wear a tuxedo and bow tie. It is fine either way. They could wear a dress as well…I had the sense that they didn’t want to stick out in the section, visually.”

For Sauerland, “the uniform thing is just an utter no-brainer. [If] you want people to sing well, let them choose their outfit.” If your ensemble has two options (tuxedo and dress), let singers choose which to wear. Providing a third, more gender-neutral, option can also create room for transgender people. Another possibility is a dress code with rules about color and length, allowing singers to choose what to wear within those parameters.

6. Provide gender-neutral restroom options in rehearsal and performance venues. In her 2016 Choral Journal article, “Creating Choirs that Welcome Transgender Singers” Ramseyer Miller says, “Post signs for gender-neutral bathrooms in rehearsal and concert spaces.” Options include single stall all-gender bathrooms or creating temporary labels for “restroom with urinal,” and “restroom without urinal.” Gender-neutral restrooms also benefit cis people whose appearance doesn’t fit traditional gender expectations.

7. Be knowledgeable about transgender singing voices. For all of us, but especially singers, voice is critical to our identity. While some transgender people take pride in having a voice that does not match our gender identity, for many, this mismatch causes intense dysphoria.AFAB (Assigned Female at Birth) people who take testosterone experience a thickening of the vocal folds and a deepening of the voice. Similar to changes in adolescent AMAB (Assigned Male at Birth) people during puberty, this is often accompanied by a period of instability and a reduced range before the voice settles. When working with transitioning singers, Steele has found it helps to schedule “a check-in once or twice a semester, because it helps educate them about their voice.” It also enables her to determine if they need to switch sections, which, she continues, “is not a real hardship on me, and they become cracker-jack sight readers!”

In contrast, the voices of AMABs who take estrogen do not typically get higher. “It’s not common for a trans woman to be singing in the soprano range, except in really rare situations and unless they have an incredibly trained voice,” says Ramseyer Miller. Choral directors can be supportive by understanding the discomfort some trans women feel about their voices and providing compassionate guidance in helping them to sing.

Directors who have limited experience with transgender singers may feel unsure of their ability to support us. But conductors already work with singers who are experiencing vocal transitions for various reasons, from puberty to aging to illness. Artistic directors “already have the tools they need,” says Steele. “We have been trained to evaluate the human voice, we can hear when it is unhealthy, and we can hear when it is dysfunctional, and that has nothing to do with whether someone is cis or trans; it has to do with technique.”

8. Be aware of how top dysphoria and chest binding can affect breathing. AFAB trans people can experience intense dysphoria connected to our breasts. To remedy this, some bind chest tissue with compression shirts, sports bras, or other materials, which can greatly reduce discomfort and improve wellbeing. But depending on the method used, tightness of the binder, how long it’s worn, and the age and experience of the singer, binding can also negatively affect breathing and, therefore, singing. Some of Steele’s singers “refrain from doing anything that might draw attention to their chests, like taking in a large breath,” she says, “so we have physical and emotional components at play.” While it is not appropriate to ask singers if they bind, just as we would not ask cis people what kind of undergarments they wear, it helps to be sensitive to the fact that some trans singers bind and may benefit from assistance with breath support and dealing with the binder, says Steele.

9. Assign voice parts and invite solo auditions based on voice, not gender expression. Voice part assignments should be handled with tact and awareness that voice can be a source of dysphoria for trans singers. “I have this fear,” says Valverde, “that if one of my trans students comes in for an audition they’re going to be pigeonholed because of their gender expression.” For instance, a singer who is not perceived as “feminine” enough may be excluded from auditioning for a “women’s” solo line, even though she could sing the part beautifully. Additionally, keep in mind that having a lower or higher voice than expected for a man or woman can be a source of great discomfort for transgender people (see No. 7). “Voice part assignments,” says Palkki, “require conversation and sensitivity.”

10. Make audition materials trans friendly. Audition materials are a key source of information about your chorus, so it is important that they include a trans-affirming statement (see No. 1) and use section names instead of gendered language (see No. 2). When collecting contact information, include a line for all singers (not just transgender ones) to write in what pronouns they use. While it’s not appropriate to ask a trans person if they are taking hormones, consider asking auditioning singers (trans and cis) if they are, or expect to be, going through a vocal transition in the coming year. “When you are accepting someone into the chorus,” says Steele, “you need to know: Are they mid-transition, and do they audition as a tenor, but they’re going to turn into a bass by mid-season?”

11. Provide “Trans 101” for all staff, volunteers, and singers. “We make assumptions that everyone in the arts is well-versed in evolving terminology” says Steele, but “you have to educate people about what [gender-inclusivity] means.” Good sources of in-person training include local LGBTQ+ organizations, sexual health centers, women’s centers, and faculty in college/university women’s and gender studies departments. Written resources, documentaries, and video blogs are plentiful. Education needs to be ongoing to account for singer and staff turnover and to stay current on recent developments.

12. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes! "It’s a messy world, and gender is a messy thing, and we’re all going to make mistakes,” says Ramseyer Miller. “In rehearsal, I sometimes find myself saying ‘gentlemen,’” Thomas admits. “Then I’ll be like, ‘Oops, tenors and basses, I’m sorry.’” Even with the best intentions, missteps or oversights will occur. If a singer says they don’t feel welcome, safe, or included, instead of becoming defensive, try seeing it as an opportunity to learn.

People inside and outside of your organization may object to changes your chorus makes to create space for transgender singers. Explaining how these changes create a safer and more welcoming environment for all singers and why that is important to your choir can be an effective strategy with those who raise concerns. “People want to do right by other people,” says Steele. “It is lack of understanding and fear that makes them resistant.”

Creating a gender-inclusive chorus is a continuous process of growth and change. “We can’t stay the same. Staying the same is just not an option, staying the same is not working for everybody,” says Palkki. “Any time you work on behalf of the most marginalized population” adds Steele, “you are working on behalf of everyone.”

Ari Agha is a researcher, writer, and life-long choral singer. They sing with Spiritus Chamber Choir and Double Treble Ensemble in Calgary, Alberta, and the Essence of Joy Alumni Singers (Penn State). An advocate of feminism, anti-racism, and trans rights, Agha blogs about gender, singing, and current events at genderqueerme.com.