Register by October 17 to Secure Your Spot!

| Registration Type | Member Price |

|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct.3) | $750 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $850 |

| Registration Type | Member Price |

|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct.3) | $750 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $850 |

| Registration Type | Member Price | Non-Member Price |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct. 3) | $750 | $850 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $850 | $950 |

Not a member? We'd love to have you join us for this event and become part of the Chorus America community! Visit our membership page to learn more, and feel free to contact us with any questions at [email protected].

| Registration Type | Non-Member Price |

|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct. 3) | $850 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $950 |

Think you should be logged in to a member account? Make sure the email address you used to login is the same as what appears on your membership information. Have questions? Email us at [email protected].

| Registration Type | Price |

|---|---|

| Individual Session | $30 each |

| All Four (4) Sessions | $110 |

*Replays with captioning will remain available for registrants to watch until November 1, 11:59pm EDT.

Member Professional Development Days are specially designed for Chorus America members. If you're not currently a member, we'd love to welcome you to this event, and into the Chorus America community! Visit our membership page to learn more about becoming a member of Chorus America, and please don't hesitate to reach out to us with any questions at [email protected].

| Registration Type | Price |

|---|---|

| Individual Session | $30 each |

| All Four (4) Sessions | $110 |

*Replays with captioning will remain available for registrants to watch until November 1, 11:59pm EDT.

| Registration Type | Price |

|---|---|

| Individual Session | $30 each |

| All Four (4) Sessions | $110 |

*Replays with captioning will remain available for registrants to watch until November 1, 11:59pm EDT.

Member Professional Development Days are specially designed for Chorus America members. If you're not currently a member, we'd love to welcome you to this event, and into the Chorus America community! Visit our membership page to learn more about becoming a member of Chorus America, and please don't hesitate to reach out to us with any questions at [email protected].

Prison choirs help inmates reconnect with their self-worth and build a sense of community –both inside and outside prison walls.

Bea Hasselmann would never use the term “cherubic” to describe her singers at the juvenile corrections facility in Red Wing, Minnesota. She knows that these young men in their late teens and early twenties have landed there because they have committed serious or chronic offenses. But she says few outsiders can begin to appreciate their circumstances.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that at the end of 2012, U.S. federal and state prisons housed more than 1.5 million people, about 1.6 percent of the adult population, the highest imprisonment rate in the world. As incarceration quadrupled between 1980 and 2000, federal and state governments were slashing prison education programs—most notably, Pell grants for higher education, which Congress and the Clinton Administration withdrew from prison inmates in 1994. This rise in the prison population resulted in part from what researcher Mary Cohen describes as “a big shift” in attitudes toward the imprisoned.

Cohen, a music education professor at the University of Iowa, has been studying prison choirs for the past decade and founded one herself: the Oakdale Community Singers at Iowa Medical and Classification Center, known as Oakdale Prison. By her count, it’s one of at least nine secular prison choirs led by certified music educators in the United States. Cohen and other observers of the U.S. criminal justice system say incarceration rates rose after 1980 in response to the public’s growing fear of crime. In turn, legislators and courts began a get-tough movement, most notably a war on drugs. The approach emphasized punishment over rehabilitation.

In the face of these challenges, a small prison choir movement took root in the 1990s. A year before the Pell grants were cut, the dean in charge of prison education at Wilmington College, a Quaker school outside Cincinnati, used grant money to start a choir at nearby Warren Correctional Institution. To lead the project, she hired Catherine Roma, founder of MUSE Cincinnati Women’s Choir. The men’s group at Warren adopted the name Umoja, the Swahili word for “unity.”

It’s no stretch to imagine there were obstacles: systemic, creative, and personal challenges that a prison setting presents to outsiders. As one of the first to face them, Roma had no model to guide her. “It was just my choral experience, my experience with MUSE, wanting to direct music that relates to people’s lives on a fundamental level.” While she was fortunate to work with a sympathetic warden at Warren, Roma encountered hostility from some officers, who wondered why inmates, whom they considered “the scum of the earth,” were getting special treatment.

Two years after Roma launched Umoja, another pioneer of the U.S. prison choir movement started on her path in Kansas. When Elvera Voth told the warden at Lansing Correctional Facility, near Kansas City, that she wanted to start a choir there, he thought it was “a crazy idea,” she recalls. “But he said, ‘Go ahead and try it.’ He came to be one of my biggest supporters.” Seventy-two years old at the time, Voth founded the East Hill Singers. Many of the 50 inmates at her first rehearsal quit when they learned Voth did not plan to do much rap or rock ‘n’ roll. But others stayed because, Voth says, they knew she’d persuaded the warden to let choir members travel to Kansas City for concerts. “Boy was that a draw,” she says. “They wanted out of that prison.”

"In a correctional facility, you're meeting people who have not been able to show passion and feeling. As choir directors, we get to see the effect of bringing music into their lives." ~ Bea Hasselmann

Hasselmann’s involvement at the Minnesota Correctional Facility—Red Wing began at a fundraising event where she happened to meet a state corrections official. A short-term commitment to put together a four-to-six week program grew into 14 years as volunteer director of the vocal ensemble Soul of Red Wing. She knows other prison music educators sometimes have trouble navigating the corrections system, but says, “I’m really supported by the staff at Red Wing.” For most of her 14 years there, the superintendent was Otis Zanders, who’s now retired. Ideas like Hasselmann’s can raise a debate in the corrections community, Zanders says: “Which is more important? Good security or good programming?” While programming that stretches prison protocol can sometimes compromise prison safety, Zanders believes “good programming makes good security. If the offenders buy in to the program, they police themselves.”

Respect is essential when it comes to getting that “buy-in” from prisoners. “To get them to trust you,” says Hasselmann, “you’ve got to respect different kinds of music. You can’t say the only worthy thing is traditional choral music.” The repertoire for Soul of Red Wing includes spirituals, pop, and occasionally rap. Once she established rapport with the young men, she found they would also open up to classics. The Oakdale Community Singers, Umoja, and the East Hill Singers have a similar range of repertoire.

Membership for these choirs commonly ranges from 15 to 40. Prisoners who join often have music experience, but others have never sung, which presents an obvious challenge. “At first they looked stunned and lost,” Voth recalls. “I think some couldn’t read words, let alone music.” Voth discovered a technique to bring these singers along. When a singer has trouble matching a pitch you’re playing for him, don’t hit the key over and over. Instead, let him sing whatever pitch he wants and then match it on the piano. “‘Oh, is that how that feels?’” Voth recalls her singers responding. “‘I’ve never felt that sensation before.’”

As part of her teaching effort, she also engaged the local choral community. Voth brought in tenors and basses from the Kansas City Lyric Opera, where she was chorus master, as well as volunteers from area Mennonite churches. She added a few more volunteers for concert appearances outside the prison. With trained singers making music alongside them, “the inmates couldn’t believe the sound,” Voth says. Cohen, who describes Voth as “the number-one influence on my research and practice with prison choirs,” emulated the approach in Iowa with the Oakdale Community Singers.

As a way to deepen their singers’ involvement in the music, Cohen and Roma both encourage original songwriting. Roma has her singers creating pieces she calls “new spirituals,” because they write about release and connection—elemental characteristics of 19th-century African-American spirituals. She records the men of Umoja as they vocalize and compose, transcribes what they’ve done and teaches them about music from the score they’ve written. “Together we learn,” Roma says. “I’m getting better aurally. Hopefully, they’re getting better at negotiating the score. I know it’s touching them because it comes from them.”

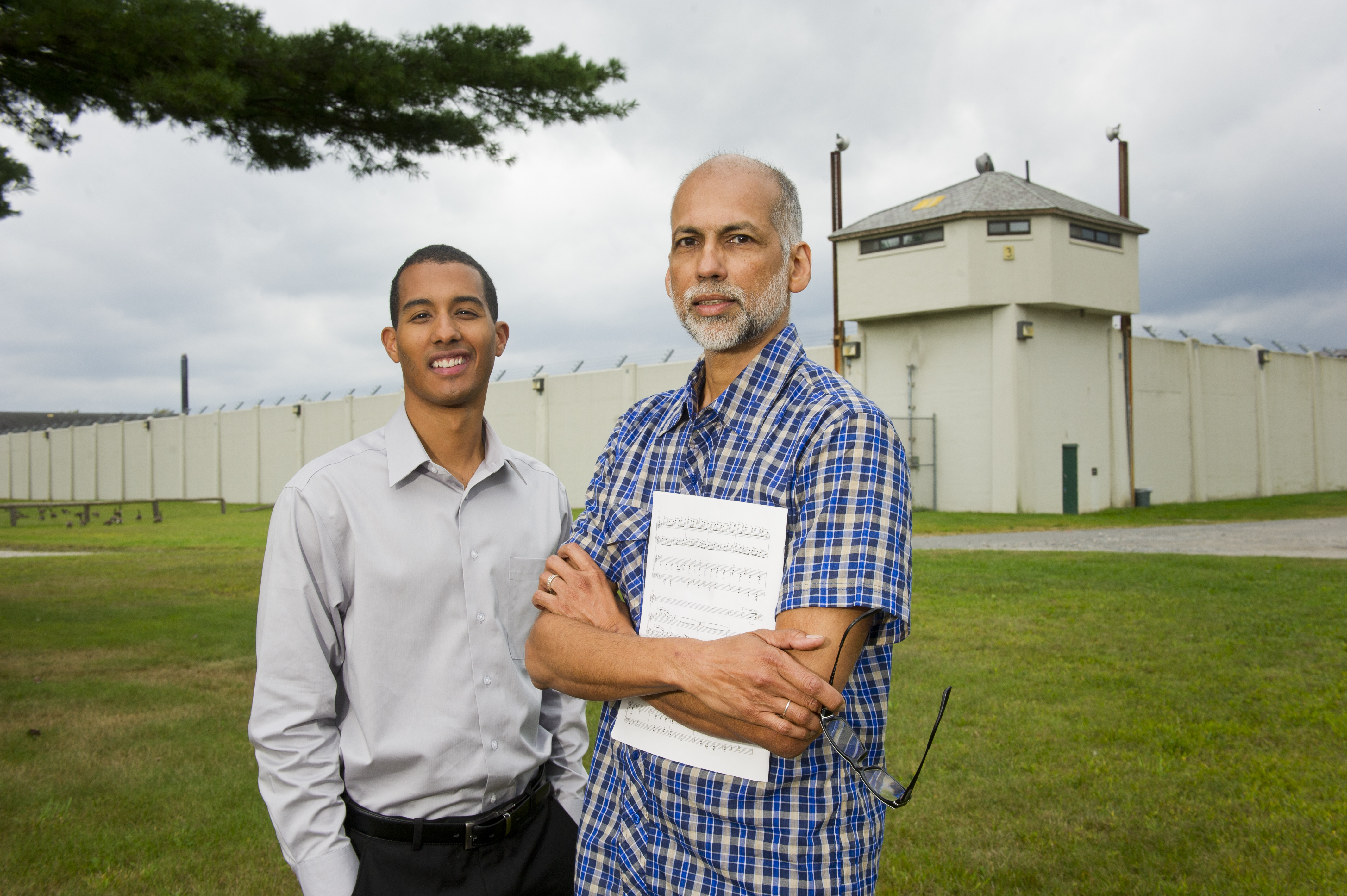

In two Boston-area corrections facilities, songwriting helps create “a passage through which other aspects of life and art can be discussed,” says André de Quadros. A professor of music and music education and an affiliate of the Prison Education Program at Boston University, de Quadros teaches music courses at the Massachusetts Correctional Institutes at Norfolk (for men) and Framingham (for women) with his colleagues Jamie Hillman and Emily Howe. “Song can provoke reflection on life, on one’s own situation,” he says.

De Quadros says there’s a waiting list for their classes, which involve group singing and movement, vocal training, and other in-depth improvisational activities related to song. “I had them sing the gospel song ‘Do Lord,’ which includes the line, ‘Do remember me, way beyond the blue.’ And I asked them, ‘What does ‘way beyond the blue’ mean for you?’” he said. “Somebody said ‘death.’ Somebody else said ‘sky.’ Then I told them, ‘Now you’re going to use that to write a poem in stream of consciousness.’” These exercises can be the key to unlocking hard-to-reach emotions. “We also used song to create a much larger writing project,” says de Quadros. “For one man, who was 52 and had suffered from childhood sexual abuse, it allowed him to bring memories back in a way he could deal with them. It allowed him to recover from a trauma of the past.”

In her research, Cohen has measured positive effects resulting from prison choir programs, and one of them is self-esteem. She says prison choir members tend to display attitudes of worthiness and competence, they show more willingness to take risks—to take part in educational programs, for instance—and they interact more meaningfully with family members. For Cohen’s mentor, Elvera Voth, some anecdotal evidence stands out. An audience at a Kansas City church gave a rousing response to one of her soloists, a man serving a life sentence. As Voth recalls it, “he started to return to his seat, but then went back to the podium and said, ‘Do you have any idea what it’s like to be given a standing ovation when you’ve been told all your life that you’re not worth a damn?’”

The significance of prisoners’ individual growth is not lost on corrections officials familiar with theories that criminal activity is related to low self-esteem. “These are men in survival mode,” says Zanders. “We’re looking for ways to move them up Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to self-actualization.”

Another benefit—one Cohen didn’t anticipate—relates to the prison environment. Informal data show that since she started the Oakdale Community Singers in 2009, relations between the staff and inmates at the prison have improved and trust has increased. She’s also learned that participants develop a sense of group responsibility. In feedback sessions, singers have told Cohen they look forward to rehearsals because they’re like “coming out of the daily mud;” the gatherings create a sense of normalcy. For the members of Umoja, Roma says, the choir becomes “an oasis of positivity and engagement and connection. It’s a beloved community within a hostile environment.”

One of Voth’s singers at Lansing admitted to her that he almost quit the choir after his first session because, he said, “‘you put me next to a black guy.’” The inmate, who was white, thought at first he’d never come back again. “‘But the black guy sang wonderfully well. The next time I sat next to a white guy who couldn’t sing a fit. So I decided I’m going back to sing by the black guy. Yesterday we had lunch together.’”

As the superintendent at Red Wing, Zanders noticed a difference: “I saw hardcore young men make miraculous changes in themselves. They could be trusted to perform in senior citizens’ homes or community events.” These experiences can literally open doors for the residents, says Zanders. Sending out the Soul of Red Wing as ambassadors provided him with a way to demonstrate that these young men could fit in if they returned to the community. “You build a ship in the harbor,” he analogizes. “You don’t know how well it floats till you get it out to sea.”

Cohen has measured community attitudes too, and her research shows that prison music programs foster greater awareness of prisoners and the prison system. She’s surveyed the members of her local choral community who’ve joined the Oakdale Community Singers—a rich data source because, Cohen says, the “outside singers,” as she calls them, are deeply engaged with the “inside singers.” Taking a step beyond the model Voth established at East Hill, Cohen brings all of her outside singers inside the prison to attend weekly rehearsals and perform concerts. She reported on their experiences in a study published in 2012 by the International Journal of Music Education (IJME), finding significant positive changes in the volunteers’ attitudes. She wrote that their experience in the group “shattered their stereotypes of prisoners.” Her study quotes one outside singer as saying, “I expected them to be in shackles and not interested in singing. I quickly learned that they were human beings, had feelings, and wanted to sing.”

Voth witnessed similar reactions on occasions when the East Hill Singers went into the community to perform. After singing at church concerts, the inmates would form a line to shake hands with people who attended. Some listeners would then approach Voth and tell her they’d never imagined an encounter like that. They’d come out of curiosity to see “bad guys,” but were surprised to discover “they’re just like the rest of us, aren’t they?”

On a few occasions, the cause of prison choral music has enjoyed wide public attention. When Voth told her old friend Robert Shaw that she wanted to stage a benefit concert, Shaw responded, “Well, Mother Teresa, how may I help?” On November 15, 1998, about two months before his death, Shaw traveled to Newton, Kansas to lead a massed chorus that included the East Hill Singers, orchestra, and 1,200 audience members in a concert and sing-along that raised enough money to launch the Kansas City-based nonprofit Arts in Prison, which uses the arts to inspire positive change among current and former prisoners. Writing in the International Journal of Research in Choral Singing, Cohen described the event as “perhaps Shaw’s greatest public testimony to his passionate beliefs about choral music and social justice.”

Umoja Men’s Chorus participated in the July 2012 World Choir Games, held in Cincinnati. They did not go to the games—Warren Correctional Institution doesn’t allow them outside—so three judges traveled the 30 miles to hear them, and reporters followed. The attention came at a good time. The State of Ohio had cut funding for prison programs like Umoja. After the Games, Roma took a break, uncertain whether the chorus would continue. But in December 2012 she was called back; Warren’s deputy warden had committed to making the program work. “They kept Umoja going,” says Roma, “because it was good for the prison.”

These directors share the conviction that making music inside prison walls is perhaps the most rewarding and important work they have done. Their experiences contain lessons they feel compelled to share with all choral musicians. In her IJME article, Cohen suggests that directors who focus only on sound miss other opportunities to benefit their singers, namely through “the rich possibilities for developing human relationships and complex aspects of self-knowledge that choral singing has the potential to cultivate.”

De Quadros encourages his students and colleagues to engage segments of the community that, in one way or another, have been walled off. “If all I did was work on conventional stages with people who were well educated, that would exclude the sick, the elderly, the mentally ill, the very poor, and the incarcerated.” He does not mean to sound “messianic,” he quickly adds, or to criticize fellow musicians. “We want music in the concert hall. But that’s not enough.”

Cohen, de Quadros, Roma, and others believe a choral program in prison can be a form of restorative justice. “As choral musicians, we say we’re changing lives in church and in school, but let’s go the next step,” Roma urges. “When you go into prison you’re transforming lives—theirs and your own—in a very different environment.”

“It’s a human rights issue,” de Quadros says. “If we think that music is an essential part of how we’re constituted as human beings, a deprivation of music is a deprivation of our rights. At what point do we lose our right to music?”

This article was adapted from The Voice, Spring 2014, a special issue devoted to community engagement.