Register by October 17 to Secure Your Spot!

| Registration Type | Member Price |

|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct.3) | $750 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $850 |

| Registration Type | Member Price |

|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct.3) | $750 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $850 |

| Registration Type | Member Price | Non-Member Price |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct. 3) | $750 | $850 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $850 | $950 |

Not a member? We'd love to have you join us for this event and become part of the Chorus America community! Visit our membership page to learn more, and feel free to contact us with any questions at [email protected].

| Registration Type | Non-Member Price |

|---|---|

| Early Bird Registration (Sept. 11-Oct. 3) | $850 |

| General Registration (Oct. 4-Oct.17) | $950 |

Think you should be logged in to a member account? Make sure the email address you used to login is the same as what appears on your membership information. Have questions? Email us at [email protected].

| Registration Type | Price |

|---|---|

| Individual Session | $30 each |

| All Four (4) Sessions | $110 |

*Replays with captioning will remain available for registrants to watch until November 1, 11:59pm EDT.

Member Professional Development Days are specially designed for Chorus America members. If you're not currently a member, we'd love to welcome you to this event, and into the Chorus America community! Visit our membership page to learn more about becoming a member of Chorus America, and please don't hesitate to reach out to us with any questions at [email protected].

| Registration Type | Price |

|---|---|

| Individual Session | $30 each |

| All Four (4) Sessions | $110 |

*Replays with captioning will remain available for registrants to watch until November 1, 11:59pm EDT.

| Registration Type | Price |

|---|---|

| Individual Session | $30 each |

| All Four (4) Sessions | $110 |

*Replays with captioning will remain available for registrants to watch until November 1, 11:59pm EDT.

Member Professional Development Days are specially designed for Chorus America members. If you're not currently a member, we'd love to welcome you to this event, and into the Chorus America community! Visit our membership page to learn more about becoming a member of Chorus America, and please don't hesitate to reach out to us with any questions at [email protected].

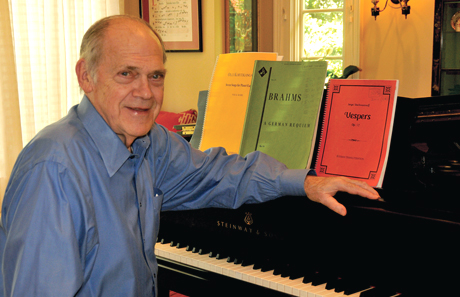

DC's "dean" of choral conductors steps down and reflects on a career that spanned a half century in the U.S. capital

Norman Scribner, founding music director of the Choral Arts Society of Washington, concluded a 47-year run at the helm with a performance of Ein Deutsches Requiem to a packed concert hall in the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts on April 22, 2012. Several thousand patrons gave him an extended standing ovation, paying tribute to his legendary contributions to the DC choral community for the last half century.

"Washington, DC is a huge choral town," says Ann Meier Baker, president & CEO of Chorus America, "but it wasn't always that way. Norman Scribner was there at the beginning of the choral boom. He's been a generous colleague, mentoring many along the way and collaborating on special projects to raise the choral profile for all."

Scribner's longevity in the U.S. capital and long association with the National Symphony Orchestra led to collaborations with a dizzying array of conductors and artists, forging formative friendships and putting him on the front line of one-of-a-kind historic cultural opportunities.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, riots broke out in Washington, DC Scribner recalls driving down to 14th Street and seeing a line of fires as far as the eye could see. He vowed to do something to promote healing in the community. "Music can be a real healing tool," says Scribner. "I committed to doing something—concerts that would bring choirs together—I had a wonderful visualization of how this could heal."

|

| Scribner (right) with composer Leonard Bernstein |

He commissioned Thomas Beveridge to write ONCE: In Memoriam of Marin Luther King, Jr., which was performed the following year by a multicultural choir in Shiloh Baptist Church where King preached when he visited DC. This first tribute led to an Annual MLK Choral Tribute that grew in size and scope in the ensuing years.

When the King holiday was established in the 1980s, CASW revised the format and moved the tribute to the Kennedy Center—Coretta Scott King attended the first of these. "I am still moved by Martin Luther King's speeches," says Scribner. "I believed history would enshrine him, that he was worthy of an annual musical celebration."

In 1971, at the request of Leonard Bernstein, Scribner assembled a professional choir to perform the world premiere of MASS, commissioned at the bequest of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis for the opening of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. This led to a lifelong friendship with Bernstein and other collaborations, including A Concert for Peace at the Washington National Cathedral in 1973.

"It was wonderful to work with a man with such incredible, natural gifts," recalls Scribner. "I became a very good friend of his. We had a way of communicating with each other and I'm convinced to this day that it was based on the fact that I was not looking for my piece of Leonard Bernstein, not fawning over him with constant requests. I was just there to provide the musical things that he needed, and I think he loved that."

Scribner has worked with every conductor at the National Symphony beginning with Howard Mitchell, but his relationship with Msitislav Rostropovich was especially close. In 1980 they collaborated in a performance (and later a recording) of the then rarely-performed Vespers (All-Night Vigil) of Rachmaninoff.

In 1993, at "Slava's" insistence, Scribner and CASW traveled to Moscow to perform Prokovief's Alexander Nevsky with the NSO before a crowd of 100,000 in Red Square.

"Boris Yeltsin was right there, sitting just below the chorus," recalls Scribner. It was in the early, heady days after the dissolution of the U.S.S.R. and Slava had to get "special dispensation" for the chorus to travel to Moscow with him. "To this day," says Scribner, "singers who went on that trip cite it as a highlight of their time with the chorus."

A keyboard artist and composer by training, Scribner moved to Washington in 1960 to become organist-choirmaster at St. Alban’s Episcopal Church after graduating from Peabody Conservatory. Like many musicians, he held several positions simultaneously to make ends meet, including that of director of the American University Chorale, where he wanted to give the students "mountaintop experiences" with the big orchestral works.

"I made an offer to the music department," he recalls. "I said, 'I'll turn back half of my salary if I can use it to pay for an orchestra, and you restore my full salary the second year.' They bought it."

While Scribner was busy producing mountaintop experiences for college singers, there was no plan in the works to form his own community chorus. When asked what galvanized him to found the Choral Arts Society of Washington in 1965, he candidly said, "Nothing really galvanized me—it happened accidentally!"

A self-described "orchestral junkie," Scribner says that as soon as he moved to DC he started going to the NSO rehearsals and got to know then music director Howard Mitchell. "I remember that first year hearing their performance of Messiah. NSO was using several church choirs, but Howard was never really happy with the choruses because they weren't properly prepared—each one was prepared independently."

Mitchell invited Scribner to find, assemble, and train the church choirs for the Messiah performances the following two years. This led to a better result, but Scribner knew it could be even better and in 1965 proposed to Mitchell that he hold open auditions and form a separate chorus for these performances. Mitchell gladly accepted Scribner's offer, and the result, says Scribner, "was a really good chorus—all of them were wonderful singers. Many, I found out later, were members of the Cosmopolitan Chorale that had disbanded the previous year."

After the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, riots broke out in Washington, DC. Scribner recalls driving down to 14th Street and seeing a line of fires as far as the eye could see. "Music can be a real healing too. I committed to doing something—concerts that would bring choirs together."

The Messiah performances were a great success. "Everyone realized this was a serious ensemble," says Scribner, "and the Symphony invited us back for a Lenten concert—we did Mozart's Requiem—and then the Cathedral engaged us to do Kodaly's Missa Brevis with a dance company. We performed three concerts that first season." So though not incorporated independently as the Choral Arts Society until fall of the next season [1966], "I always call that year number one," says Scribner.

Even with a newly formed chorus to lead, Scribner didn't look too far into the future. "I did not do this with any intent of it being a permanent choir—it was just so well received it developed a life of its own right away, which I was happy to go along with." He asked a lawyer and several other members from the choir to form a board and they were off and running.

Lest it all sound too storybook, it wasn't long before they encountered the "intractable challenge of raising money," recalls Scribner, prompting the organization to look beyond the singers deeper into the community for board leadership and funding. They had early success securing three major sources of regular funding, which went a long way toward establishing a foundation of stability as the organization quickly grew and took on an array of artistic challenges, including collaborations with world-renown artists, recordings, broadcasts, and international tours.

The demands of leading a major performing arts organization led to a career that Scribner had never envisioned, but never shrank from. "It happened gradually over time," he recalls. "It was 15 to 20 years of building before I realized that I had a vested interest in making the chorus permanent, not just a mom-and-pop thing that disappears."

Scribner and the board saw eye-to-eye about ensuring CASW's future and have worked together to build the underpinnings of a resilient organization. "We have the endowment, we have the infrastructure, we have the rules and regulations and bylaws," says Scribner. "Everyone knows their responsibilities and authorities...the organization is protected with a system of checks and balances—this system has always kept us on track."

Throughout CASW's formative development, Scribner kept his "tentacles" in other things, including continuing to serve as organist-choirmaster at St. Alban's, a position he held for 47 years until 2007. Scribner was commissioned by the United Methodist Church to write Love Divine, premiered at the church's General Conference in 1984.

The son and grandson of Methodist ministers, Scribner says faith has played a strong role in his life. "Growing up I was constantly in church—it forms the bedrock of my lifelong narrative," he reflects. "My faith is inseparable from my music—they are a tightly woven braid. The biggest window on my spirit is music—it's the canon for my life."

Facing retirement with the organization he founded 47 years ago, Scribner appears sure of his decision and very grounded. "You just feel little internal changes in yourself and your whole chemistry adjusts," he says. "I noticed a change at 65 and I'm noticing a change as I approach 75." A few years back, as CASW approached middle age and aimed to secure the organization's future, the board did their due diligence by adopting succession plans for the top artistic and executive positions, providing a road map for a smooth transition when the time came.

When Scribner announced his intent to retire two years ago, that kick-started a process that ended in March of this year with the appointment of his successor, Scott Tucker, choral director of Cornell University. Scribner, who did not participate in the search for his successor, says his one wish for Tucker is that "he have the same degree of support that I've had all these years." He does not want to be "an intruder in the process. The organization is in such good hands and Scott is such an incredibly wonderful person."

"In a career field that turns a sometimes white-hot spotlight on its proponents, Norman Scribner deflects the attention in a refreshing, sometimes surprising, way," says Ann Meier Baker. "Although he has mingled with and been on a first-name basis with superstars in classical music, it all comes down to the music for him, to the reverence he feels for it."

Speaking of his two favorite composers, Bach and Mozart, he says, "I cannot fathom how they made the music they did. There are a huge number who fall just below them that have profoundly affected me. I have a visceral, physical reaction to Mahler, the magical, spiritual verity of his music."

Scribner has recently turned his attention to early music, particularly the Renaissance, unearthing scores long buried in the rich treasure trove of the Library of Congress. When asked what music he would be making and with whom come this time next year, Scribner said, "I honestly don't know. It may be nothing, or it may be all kinds of stuff."

So continues the canon of a musical life well lived.